Well I’m in London now, writing this from under a doona in bed at my cousin Alex’s place in East Acton. I keep waking up really early – don’t know if it’s the remnant of jet lag or just the unfamiliarity of my surrounds, but I seem to be keeping an uncharacteristic acquaintance with the early hours of the morning!

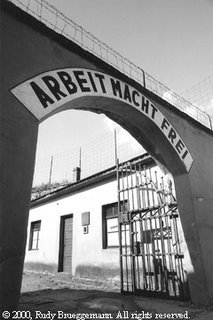

It has been weighing on my mind that I need to write about Terezin. Going there was like remembering a nightmare that someone had told me about. The familiarity of its buildings, the names of the streets and squares and barracks, even the distinctive black and white striped paint above the entrance to a the Small Fortress was all like horrible déjà vu. Will and I caught the bus from the Metro station at Florenc out to Terezin. It’s a 61Kc 1-hour journey beyond the outer limits of Prague and into the countryside. It was bitterly cold, and the fields were a dirty white from the ice and snow. The sky was grey, and we had a sort of detached feeling that the day might be a little bit unpleasant. But as we drew near the town, my tension grew. When the Star of David-shaped walls and painted archway of the Small Fortress passed by the window of the bus, I began to realise what we’d got ourselves in for. We then drove over a bridge over the Ohre river, around a corner, and through the ramparts into the deserted Town.

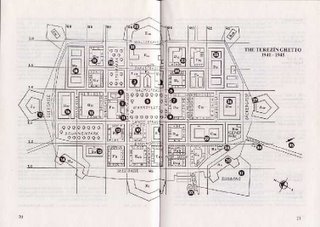

For the uninitiated, the Terezin is a fortified town – a fortress – that was built in the 1780s by Emperor Joseph II and named for his mother, Maria Theresa. It was meant to protect against invasions from the north west by the nasty Prussians, but was never actually used in any combative military capacity. Terezin comprises a small, picturesque town meant to house the soliders and their families, surrounded by beautiful open planes and mountains in the distance. Its streets and squares are pretty and well laid-out. Few hundred metres from the Town is the Small Fortress, used to house political prisoners, enemies of the Habsburg Monarchy, and Prisoners of War during WWI. Because of its handy position between Western Europe and the extermination camps of the East, the Nazis pinpointed it as the perfect strategic place to gather or ‘concentrate’ some of the European Jews before sending them onwards to the Polish camps such as Auschwitz-Birkenau and others. So on 24 November 1941, the first transports of Prague Jews headed for Terezin - Theresienstadt, as the Germans knew it.

The conditions there were awful and many thousands of people died, but everything that is sad or evil or twisted about the town is made so much worse by what happened there in June 1944. After much to-ing and fro-ing between the Nazis and the International Committee of the Red Cross in Geneva, a Red Cross delegation was permitted to visit the camp. In preparation for this visit, the town underwent a ‘beautification’ process. To alleviate crowding, the top level of the 3-tiered bunks was sawn off, and one third of the detainees were sent to Auschwitz for immediate liquidation. The streets were cleaned and buildings painted. Children were given extra rations in order to appear healthy and robust to the delegates, and the camp commanders chose the fittest, best-looking young people to play a role on the day of the visit. Cafes, shops, a library and sporting events were concocted out of nowhere. There were musical performances and concerts, and many writers, thinkers and academics were briefed to discuss high-brow philosophical and intellectual topics within earshot of the visiting Red Cross delegation. Children were told to moan good-naturedly about going to school and having to eat high-quality imported sardines almost every day. Basically, the stage was set for one of the biggest shams in modern history – the conversion of Terezin into a Potemkin Village.

In summary, 23 June 1944 came and went, and the Red Cross took the bait hook, line and sinker. The report written by Dr Rossel is a stunning testament to the convincing charade, and his lack of further inquiry has been condemned by many after the fact. The Nazis were so pleased by the effectiveness of the sham that they took it upon themselves to make a propaganda film called ‘Hitler gives a Town to the Jews’. The fears of the international community were alleviated, they let themselves off the hook, and meanwhile thousands died at Theresienstadt, and many more thousands were funnelled through its walls and on to the Eastern extermination camps.

I will write more about this later. Stay tuned.

j x

2 comments:

i think you summed it up nicely by calling it god forsaken

I don't know what to say...and that's pretty much how I felt when I went to Auschwitz (dumbstruck). I'll never forget watching Japanese tourists film video inside the showers...we spent about 2 hours at Auschwitz, and that was more than enough - it was a place that should be visited only to remember what humanity is capable of...I felt the ghosts of violence, pain and misery everywhere I turned.

Post a Comment